I loved the level of detail that you spent on the government. Do you have a process that you use? Perhaps you can write it down and share it with your peers?

So, in this case, I've been particular blessed to have a worldbuild/brainstorm partner, in Dan Fawcett. Dan is far more of an academic than I am, and while I'm pretty good at the research side of worldbuilding, he's really the master. He's the one who first turned me on to Jared Diamond's works Guns, Germs & Steel and Collapse, both of which I consider required reading for worldbuilders.

As to the process itself: Dan and I hashed out the real broad-brushstrokes, soft-import, high-concept stuff of each nation/cultural area. Then we came up with tour National Document template-- something I want to rework to a degree, but that's neither here nor there-- which I would use to write up each nation*, and then pass it off to him. He'd tear into it, usual with questions about specifics, which would help us drag each culture away from its broad-brushstrokes, soft-import, high-concept origins and give it something unique.

As to the process itself: Dan and I hashed out the real broad-brushstrokes, soft-import, high-concept stuff of each nation/cultural area. Then we came up with tour National Document template-- something I want to rework to a degree, but that's neither here nor there-- which I would use to write up each nation*, and then pass it off to him. He'd tear into it, usual with questions about specifics, which would help us drag each culture away from its broad-brushstrokes, soft-import, high-concept origins and give it something unique.In the case of Waisholm, a big aspect was making it something that Druthal wasn't. Druthal is a parliamentary monarchy, a relative enlightened state for a fantasy/renaissance type of culture, and I wanted Waisholm to be... not so much harsher, but further back on that path. And more to the point, a place where small-group insularity and in-fighting was the main thing holding them back. So this required the throne to be a weak title compared to the local lords, and a place where "civil wars" are a relatively common part of their history. So this required creating a government system where fealty and identity function strongest at the local level.

The question was about achieving that level of detail, which I attribute to the national document, which is relatively comprehensive (what I posted came from sections on government, military, law and criminal activity, for example), and it went through that question-and-respond process to make it stronger.

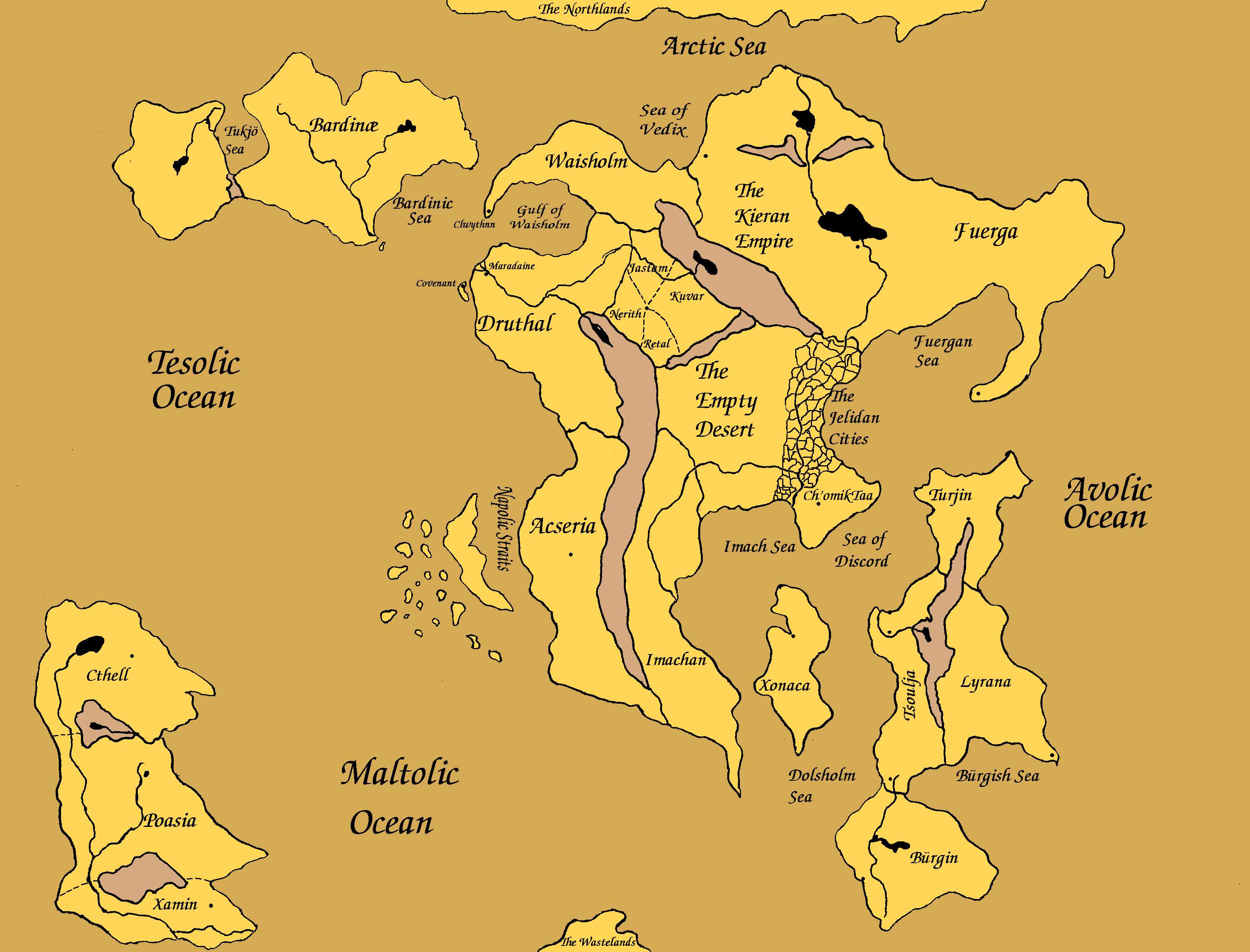

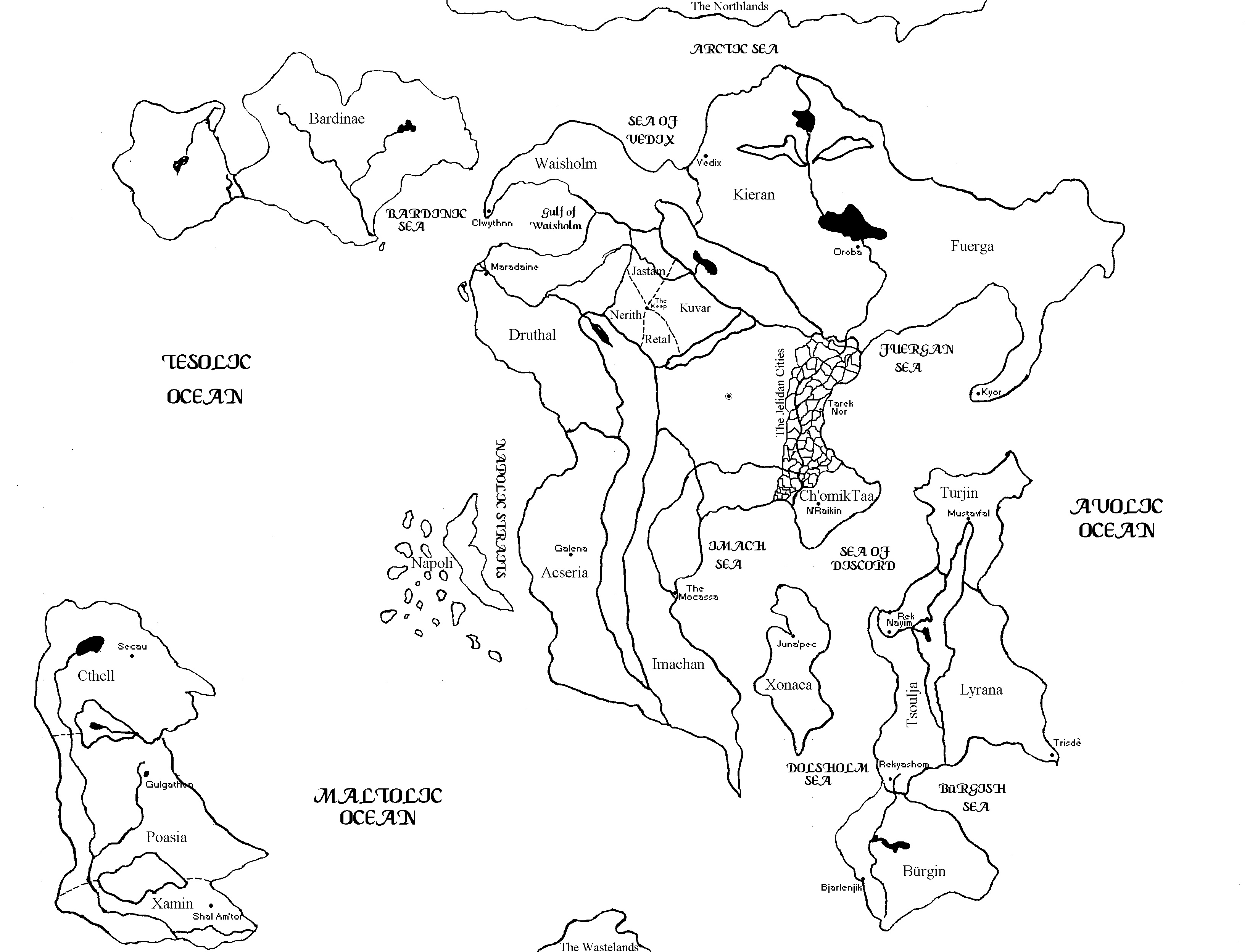

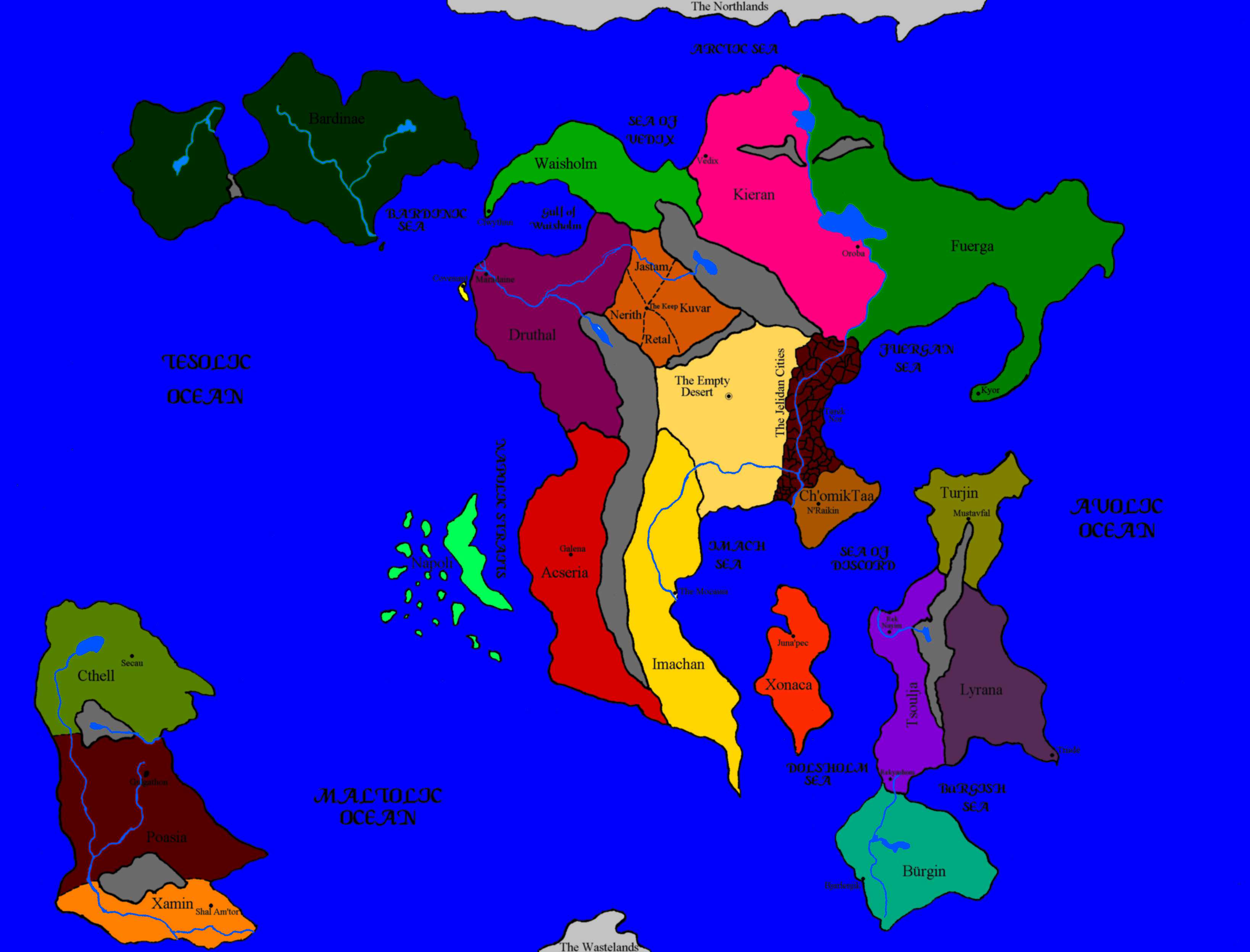

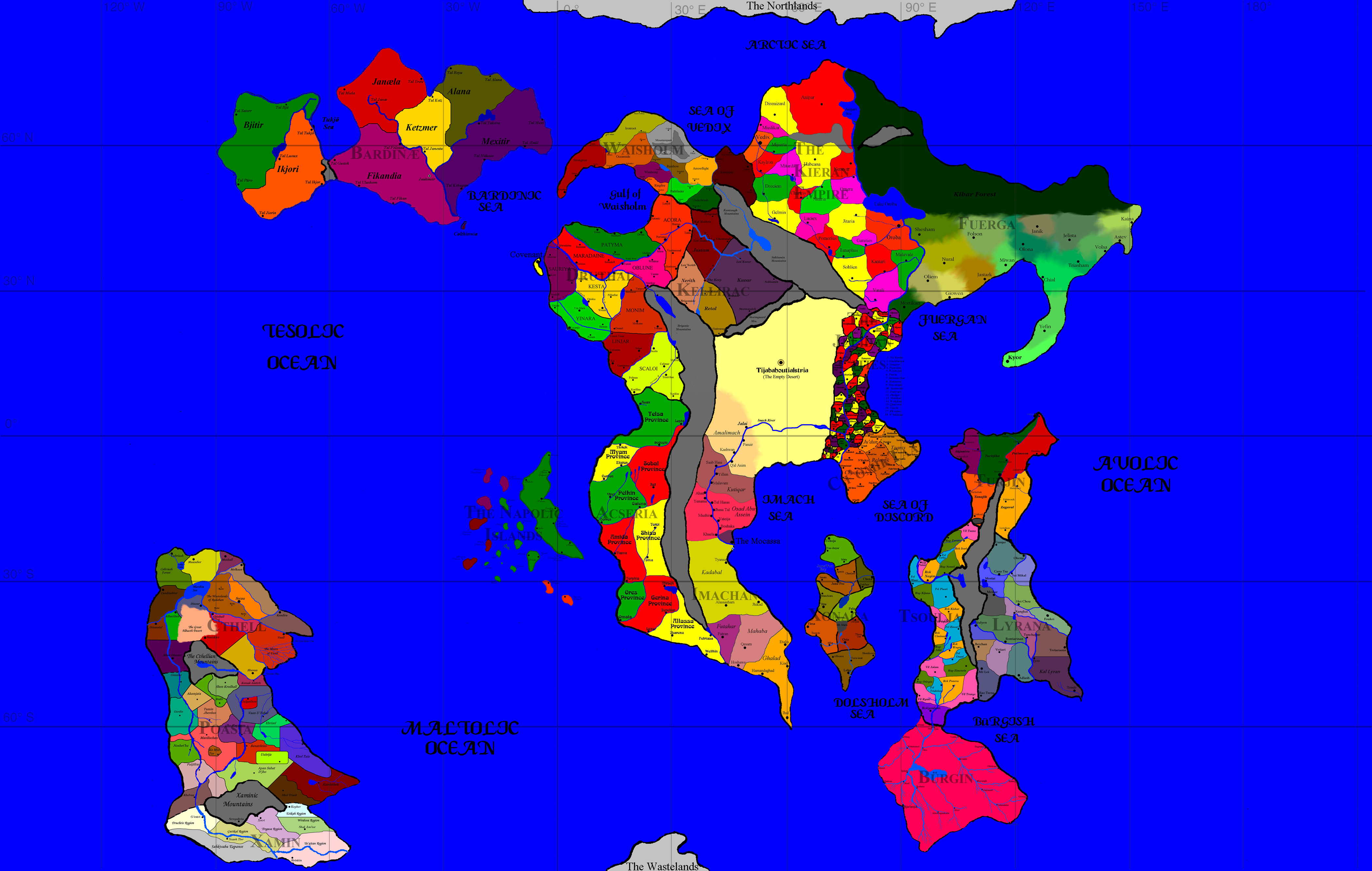

How did you create the actual map?

The maps have had a long history-- the initial map started nearly twenty years ago, hand-drawn of the whole world. I eventually got that scanned (and this was in the 90s, where "getting something scanned" meant going to Kinkos and giving them your 3.5" disk to put the scan on), and started making more detailed maps of each respective part. Over the course of time, as the capabilities of the computers and drawing programs I had access to improved, so did the details of the maps.

So maps that had their origins in hand-drawn, followed by MS Paint, have now been worked over in PhotoShop 6. There are some that I haven't updated as much as others, of course-- Druthal itself has had the most evolution-- but on the whole it's a far more advanced and detailed work. And, more to the point, more advanced and detailed than it could have been back then. Somewhere in the house I still have the 3.5" floppies that have zipped-up files of the maps-- i.e. it took multiple disks and compression to carry it all. Now I have map files that would have made the old computer explode.

--

*- There are a few nations he did the initial write-up of, though I don't recall which ones off the top of my head.